The following is an excerpt from Dr Kevin Roy’s book “Zion City RSA” with a few alterations, additions and subtractions by me to make it more suitable for the blogging format. For the full bibliography see the bottom of the article

A profound struggle took place in the mid-1800’s for the Dutch Reformed Church. This struggle occurred between defenders of traditional orthodoxy and proponents of a more modern rationalist theology. Before the establishment of a theological seminary at Stellenbosch, young Afrikaners desiring to enter the ministry studied in Holland, where they came under the influence of modern theological trends which were critical of traditional orthodoxy and sympathetic to the spirit of rationalism characteristic of the Enlightenment.

A good example would be T. F. Burgers. Burgers went to Holland to complete his theological studies at Utrecht in 1853. By the time he returned to take up the ministry in the Karoo town of Hanover he had moved away from his early pietism to a more modern theology, speaking out against revivalism in 1859. There were other ministers of like mind who hoped to steer the Church in a new direction. Things came to a head in the synod meetings of 1862, which one of its delegates, Frans Lion Cachet, described as ‘a struggle between faith and unfaith – a life and death struggle resulting from the unbelief which is proclaimed as truth in Holland and in the Dutch academies.’[i]

A good example would be T. F. Burgers. Burgers went to Holland to complete his theological studies at Utrecht in 1853. By the time he returned to take up the ministry in the Karoo town of Hanover he had moved away from his early pietism to a more modern theology, speaking out against revivalism in 1859. There were other ministers of like mind who hoped to steer the Church in a new direction. Things came to a head in the synod meetings of 1862, which one of its delegates, Frans Lion Cachet, described as ‘a struggle between faith and unfaith – a life and death struggle resulting from the unbelief which is proclaimed as truth in Holland and in the Dutch academies.’[i]

The liberals proposed that representatives of congregations outside the Cape Colony (all of whom were more orthodox-minded) should be excluded from the synod. The synodical rejection of this proposal was overruled by a Supreme Court decision. Thus the orthodox element in the synod was weakened. A charge was brought against T. F. Burgers that he denied the personal existence of the devil, the sinlessness of Christ, the resurrection of the dead and the survival of the soul after death. A commission was appointed to investigate the charge.

During another session of the synod it was proposed that ministers should positively defend the Heidelberg Catechism, one of the doctrinal standards of the DRC. To this J. J. Kotzé of Darling replied he could not defend question 60, where it was taught that the believer ‘still tends towards all kinds of evil.’ Kotzé was ordered to withdraw his statement, which he refused to do. When disciplinary steps were enacted by the synod against Kotzé and Burgers, both took their cases to the civil courts, which found in their favour and revoked the actions of the synod.

While the liberals prevailed against their orthodox opponents in the courts, the conservatives eventually won the battle for the church. By keeping close control over the seminary at Stellenbosch and by instituting carefully defined procedures for admitting candidates to the ministry, the conservatives were able to exclude modernist tendencies from the ministry and maintain an adherence to the traditional confessions of the church. Andrew Murray served as moderator of the DRC during this struggle and also personally undertook the defence of the church in the various court cases to which it was summoned.

The Same Thing in Anglicanism

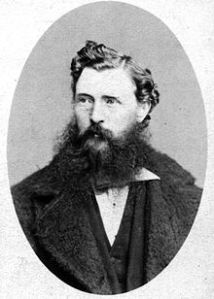

The Anglicans experienced a struggle against theological modernism very similar to that of the Dutch Reformed, and at about the same time. At the very centre of the Anglican conflict was the impressive  first bishop of Natal, John William Colenso, whose views and actions evoked admiration, exasperation and dismay from friend and foe alike. Born in 1814 into a poor family, he had to work hard to gain an education and finished his studies at Cambridge.

first bishop of Natal, John William Colenso, whose views and actions evoked admiration, exasperation and dismay from friend and foe alike. Born in 1814 into a poor family, he had to work hard to gain an education and finished his studies at Cambridge.

Indicative of his ability, he compiled and published an Arithmetic for Schools which was successful enough to help him out of financial difficulties. At Cambridge Colenso was strongly influenced by the universalist views of F. D. Maurice and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. After serving as the rector of a small country parish for a number of years he was offered and accepted the bishopric of Natal in 1853. The following year he made a preliminary visit to his diocese, recording his impressions in a little book called Ten Weeks in Natal. Colenso did not hesitate to adopt and express clear views on controversial subjects.

When Colenso settled in Natal in 1855 he established his headquarters about five miles from Pietermaritzburg at Bishopstowe, or Ekukanyeni (the place of light) where he remained until his death. This place, he envisaged, would become a great mission centre from which a Christianizing impulse would radiate to the entire Zulu nation. It was planned on a grand scale and developed with tireless energy. It contained a forge, a carpenter’s shop and a translation centre. There was also a printing office and a boarding school where the sons of chiefs should learn Christian leadership with grammar. Colenso proved to be a gifted linguist. In a few years he not only learnt the Zulu language but compiled a Zulu grammar, dictionary, readers, and manuals of instruction in Zulu – in history, geography, astronomy, and other subjects. He also translated Genesis, Exodus, Samuel, and the entire New Testament into Zulu.[ii]

Colenso needed considerable funds in the development of his mission and looked to the state to provide a portion thereof. Unashamedly imperial in his approach to evangelization, he regarded the British Empire in 1854 as superior to ‘the empire of ancient Rome in the days of its grandeur’ and considered it as an instrument of ‘God’s Providence working to Christianize the world.[iii]’

In 1861 Colenso caused a huge stir when he printed at Ekukanyeni a commentary on Paul’s letter to the Romans in which he attacked the teaching of penal substitution, denying not only that Christ had died to placate an angry Father, but also that God has any righteous anger against sin at all. He also held that all men are justified in Christ from their very birth hour; baptism is merely a recognition and proclamation of this fact. The gospel is preached to the heathen, not to convert him but to set before him a pattern of love so that he may follow it.[iv]

The influence of F. D. Maurice is clearly discernible here, but Colenso lacked his tact and was more impetuous and aggressive in advancing his views. Gray was alarmed by the book and begged Colenso to keep it back for at least a year and consult his friends. Refusing to withdraw anything written in his commentary on Romans, Colenso proceeded to publish in 1862 the first part of a critical work on the Old Testament – The Pentateuch and the Book of Joshua Critically Examined. Convinced on the grounds of its bad arithmetic that the Old Testament could not be verbally inerrant, Colenso concluded that it was no more inspired than the words of ‘Cicero, Lactantius, and the Sikh Gooroos.’[v]

By this time there was widespread outrage against the views of the bishop of Natal. On the basis of his works, nine charges of heresy were brought against him, and in 1863 he was deposed from his see by Gray, who presided over a court consisting of the other three South African bishops. This sentence was followed by one of solemn excommunication in 1866. Colenso appealed to the courts against the sentence of Gray, claiming that the latter had no right to depose him as he was responsible to the British crown alone. This appeal was upheld by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in 1865, so Colenso was reinstated as Bishop of Natal. Furthermore, he was awarded for life the income from the endowment of the See of Natal, and the trusteeship of all diocesan property acquired since his consecration. Despite his resounding victories in the courts, Colenso experienced increasing difficulty in maintaining his considerable projects and getting suitable clergymen for his diocese. Gray consecrated an alternative bishop for Natal, and twenty years of schism followed. After the death of Colenso in 1883 nearly all the churches and clergy of Natal returned to unity with Archbishop of Cape Town.

In the long run however it appears that theological liberalism, the seeds of which were planted in the mid-1800’s, has won out at large in much of the Dutch Reformed and Anglican traditions. A weak view of the authority of Scripture has eroded many of the mainline denominations, with effects being felt among Methodists, Baptists and Prespyterians to name a few.

_________________________________________________

Thank you Tyrell. I appreciate your blogs on this subject . To understand the present spiritual dilemmas we need to understand the past . We reap what we have sown . I know that this goes very much against the current post modern trend of ignoring the past .